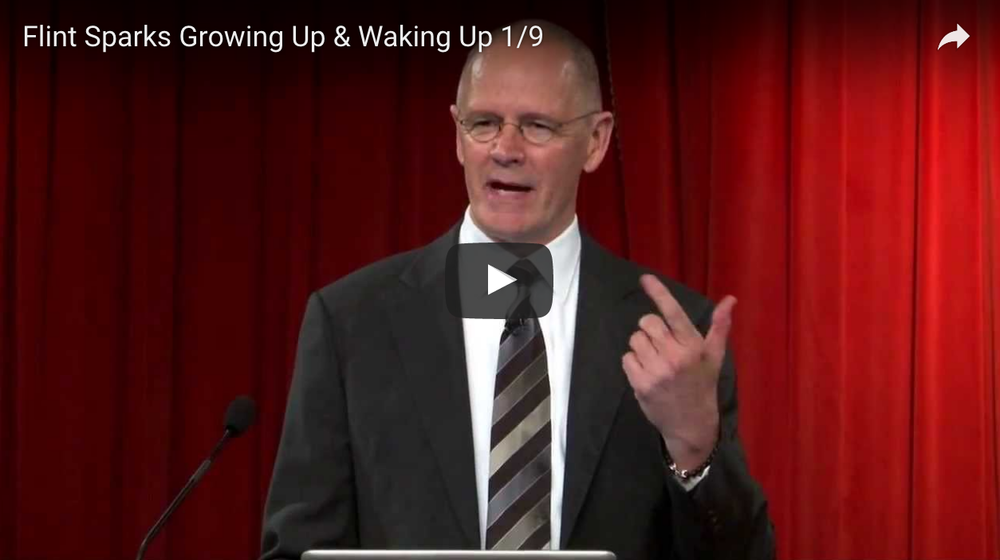

Early in 2017 I was asked to offer the keynote for the annual celebration and fundraising event for an organization in Austin called iACT —

Interfaith Action of Central Texas — to be presented on September 26, 2017. The mission statement is simple:

iACT cultivates peace and respect through interfaith dialogue, service and celebration. The annual event, “A Night Under One Sky” was to focus on spiritual friendship and I agreed to speak. As I began to prepare my talk I found that I was unable to craft the usual, and expected, speech about unity and oneness. The current situation in our country didn’t seem to call for this kind of talk which would no doubt be enjoyed by everyone but ultimately remembered by no one. I couldn’t bring myself to focus on the “One Sky” part of the celebration. Instead, I chose to focus on “the Night.”

A bit more about the context of the event: It was held in a beautiful sculpture garden in which guests could wander along trails, along a stream, and through woodlands. Along the way they would encounter the lovely image by

Charles Umlauf (1911-1994), a beloved sculptor from Austin. Knowing this will help you understand some of the references in the body of my talk which follows. I am sending what I wrote and how I ultimately delivered it. I have been strongly encouraged by many people to publish it (possibly in an edited version) but I have not felt like I knew the appropriate place. So, here it is. I hope it may speak to you in some way that might be helpful.

With my warmest wishes for peace and healing — everywhere and for everyone.

Flint

We find ourselves in such a confusing, unnerving moment, but this evening we are embedded in this enchanting landscape, inhabited by these silent, beautiful images of Charles Umlauf. This is their garden, and tonight they allow us to join them in silence and stillness, even if we pause for only a moment with each one, captivated by their exquisite presence. Our task now is to open to the warm embodied presence which comes from the deepest well of silence within and between us. Of course, the intimate touch of human presence can only arrive if we stop and allow life to catch us — to flow through us, simply and fully…humanly…through our marvelous animal bodies.

I want to pause to offer an apology at the outset. I love to speak directly, with a personal, intimate connection. It is what I know and who I am. But tonight, as you can no doubt tell, I have uncharacteristically written what I hoped to say. Very early yesterday morning I woke up in Geneva, Switzerland. By late morning I was in London. By afternoon rush hour I was in Austin. Yesterday was a long travel day, but I did not want to miss this night with you and I wanted to be clear. So, this is what I composed as I imagined our brief and precious time together. And as I stand here now I can feel what an inspired and inspiring group you are, filled with goodness, coming together to celebrate in this way — a Night Under One Sky. And I want to focus on the night — darkness and light playing off each other as we gather as humans have always done, out of a primal necessity to be close in the dark. Our hearts require each other.In knowing that in order to truly flourish, I require you. And this is at the heart of iACT.

“The transformation of the heart is a wondrous thing no matter how you land there,” the artist and writer Patti Smith famously said. And for many of us here tonight, the work of spiritual and social transformation is our dream, our calling, or our vocation. I would assume everyone here came tonight because somewhere deep inside, you long for the world to be lovingly transformed in some way. We long for a kind word. A compassionate world. A world full of wisdom and generous care. A patient and spacious world in which everything and everyone is welcomed.

Although I would wager that my assumptions about us are reasonably accurate, I feel a bit of discomfort, as if I am beginning to go slightly astray by making this list of admirable qualities. Here are my concerns.

There can be a hidden seduction in consensus, an unseen perversion of purpose in holding too tightly to any one position, a subtle entrancement invited through commonality of thought, and an unexpected form of violence in a social worship of one-ness.

So, I now have to apologize for a second time; this time for being so blunt. I was not invited to guide us down a road of cynicism or despair. We certainly have more than enough of that at this moment. I promise I am not arguing for some intellectual erosion of faith, care, or everyday hope. I only ask that we enter our conversation honestly and clearly forewarned.

I speak in this way because I am concerned that we don’t have time to waste. Consoling each other only through shared agreement won’t transform the broken-heartedness and shattered relationships of the world. We must venture to the shadowy edges of our understanding, of our comfort and of our comprehension, in order to come to appreciate the startling diversity of who we really are, what we truly stand for, and what we are capable of in this world.

At bottom we are here to celebrate our unity and to reflect the light of our genuine goodness that flows through the work of iACT. But I am concerned that in doing so we might easily and unknowingly neglect the dark…and I am convinced that neglecting the dark is destroying us. I don’t want to fail you or miss the moment. I feel called to more. I am calling you to more.

Here is Rilke, writing from his time in a Russian Orthodox Monastery:

You, darkness, of whom I am born —

I love you more than the flaming light

that limits the world

to the circle it illuminates

and excludes all the rest.

But the darkness embraces everything:

shapes and shadows, creatures and me,

people, nations — just as they are.

It lets me imagine

a great stirring presence breaking into my body.

I have faith in the night.

I have a vibrant and abiding faith in the great incomprehensible web of existence in which we are held. This is the space into which we are born and into which we will inevitably return. It is the field of all goodness and sorrow, of love and hate, of grief and celebration—our one unbound heart and mind which we strive to embody through the spiritual practices of our various wisdom traditions and to express in our communities. In our Zen liturgy we chant a beautiful phrase which comes within a longer verse — “Vast is the robe of liberation, a formless field of benefaction.” This virtual robe of liberation is what surrounds us and the field of beneficence is our home. By whatever name, it is vast and liberating. And yet, this “stirring presence” that Rilke described breaking into his body, and the “formless field of benefaction,” in which we rest, is more than the magnificent light of the Divine, the glow of the Great Mystery, the warm smile of God, or the unbound love of Universal Consciousness. And please be assured, I embrace this light and love, as the very essence of goodness at the heart of our lives and our practices. This perfect and brilliant radiance is precisely what we are celebrating tonight and where we channel our energies in response to the call for social action. But I am concerned, in that rich glow, that we may be blinded to the very shadowy requirements of our quivering animal bodies, our frail and shaky humanity, our fierce and messy mammalian life force which is our ground of being.

Humans have always sought a way to tolerate the primal vulnerability we face against the sheer mystery — the incredible awe — of simply being alive. This earthly embodiment is what we must reclaim and utilize wisely if we are to survive as a species and as a planet. This is what makes organizations like iACT essential. We can be a stronger and more penetrating voice for the radical inclusion of faith and courage in this generous embodiment, and we can enact these vital and liberating qualities where they are most needed if we do not turn away from our most vulnerable longings.

I am pointing to the essence of spiritual life because without our bodies — the exquisite expression of creation and human incarnation – and without a wholesome environment in which the bodies can strive and thrive — there is no life of spirit, there is only a slow and painful, self-created diminishment of spirit and, as we are witnessing all too painfully, the death of civil humanity.

Humans have very sophisticated brains, and we are singular in having the most well developed pre-frontal cortex. It is why we have these skulls which are peculiar among primates. We are a species of mammal who bring their young into the world long before they can be on their own. We are not on our feet running with the herd within minutes because our survival does not depend on it. But our survival does depend on rich enduring relationships. As a result, we have to attach strongly and remain attuned deeply in order to support maturation into resilient human-being-ness. And the part of our brain that fills this frontal protuberance is working continually, like the spinning, searching signal on your phone or laptop, to find a connection. It is scanning to answer three crucial questions constantly — many times every second of our lives:

1.

Are you there? We naturally look for a caring figure to whom we can attach, not just as infants, but throughout our lives.

2.

Do you hear me or see me? We long to attune with others emotionally because it is the way we regulate our bodies, hearts and minds.

3.

Do you choose me? The heart of it all — am I loved?

Every human yearns for a warm response to these questions in engaged action, in living form, in fleshy human relationship. And much of what we are now horrified by in our world are the consequences of the ways in which these signals have found no response, no answer, no connection. There are so many people lost in the shadows and we are startled as they begin to emerge into view and with them come the demands and pains of their unmet longings.

I am not talking about the failure of parenting here, I am speaking about the ways we relate to each other as adults every day. Leaders at every level, from those in the smallest local enclave to those on the largest and most visible national and international stage—if they appeal to these essential qualities of inclusion and connection, they will find friends and ardent supporters. No matter how disaffected or marginalized, if you offer someone hope that they will be seen, heard, and included, and if you offer them something to do that will make a difference—any difference— in a world that they have given up on, and if you promise, even falsely, that they will be celebrated alongside others for joining in, then they will join you. And no amount of rhetoric or rebuke from another perspective about how misguided the group or its leaders are, will change that reality. Powerful meaning and meeting in human relationships is what matters, even in what we might judge as base or even savage relationships. An invitation to join with others in a way that makes sense to you trumps despair and isolation, meaninglessness and impotence.

We have to go into the dark, the shadowy aspects of ourselves, of our closest and dearest relationships, and these complex communities of our world. This will likely make us uncomfortable or even terrify us, but the result of not looking, not listening, not connecting, and somehow missing something important in the dark has become equally terrifying. Hopefully we are awakening to face who we really are and who the “others” are, and the pain that comes with even making such distinctions. We must make contact with, and even better, friends with, the shadowy elements of both ourselves and those around us.

If It Is Not Too Dark

~ Hafiz

Go for a walk, if is not too dark.

Get some fresh air, try to smile.

Say something kind

To a safe looking stranger, if one happens by.

Always exercise your hearts knowing.

You might well attempt something real

along this path:

Take your spouse, lover in your arms

The way you did when you first met.

Let tenderness pour from your eyes

The way the sun gazes warmly on the earth.

Play a game with some children.

Extend yourself to a friend.

Sing a few ribald songs to your pets and plants—

Why not let them get drunk and wild!

Let's toast

Every rung we've climbed on evolution’s ladder.

Whisper, "I love you! I love you!"

To the whole mad world.

Let's stop reading about God—

We will never understand Him.

Jump to your feet, and wave your fists,

Threaten and warn the whole Universe.

That your heart can no longer live

Without real love.

Hafiz always grabs us with a joyful invitation. In our current circumstances however, this invitation seems a bit timid. In fact, the title given to this piece, “If It Is Not Too Dark” hedges a little. It is very dark, and we are called to act anyway—to go for a walk, to exercise our heart with strangers, to love and to play, and to celebrate. But then he turns: “Jump to your feet, and wave your fists, Threaten and warn the whole Universe,” About what? “That your heart can no longer live without real love.”

What does that mean in your life and in my life? What can we actually do?

See each other. Acknowledge each person’s truth and presence, even if you are dismayed by what you encounter. Learn from everyone or at least about them. Someone will find them and connect, and that is the person or group who will have the most influence. Everyone wants someone there - really there - so they feel truly met. Failing that, most of us can easily escalate into reactive or protective behaviors in a feverish attempt to grasp at what we lack or cover our fear.

Listen to each other. Really listen for meaning, not agreement; listen for vulnerability and the signs of suffering, not so you can “help,” challenge or change. Allow people to speak their truth and to be reflected so they can know themselves, and so you can know yourself as something more than your most cherished personal perspective. What you don’t know or turn toward will hurt you — and others.

Cherish everyone and everything as if it were your own body—because it is. Turning toward the shadows can be frightening, but turning your back on the darkness is dangerous. And we are all in this together.

Boundaries are essential for life to flow in balance. Rivers need banks and a fire needs a container. Without the boundaries they can be destructive. With proper boundaries they serve and nourish. There is such a thing as foolish compassion and there are real dangers in the world. It is crucial to know your limits because it helps contain and focus your strengths. Sometimes it is wise to put some distance between you and another person or group, even as you hold them warmly in your heart.

Be patient with yourself as you stumble and fail, but don’t give up. Accept your impotence without apology. Soften into strength and be kind to yourself, another way to describe self-compassion.

Practice flexibility and humility: In the words of the well known family therapist Carl Whitaker…

Fracture role structures at will and repeatedly: Entrenchment is not a nimble place from which to respond to the world.

Learn to retreat and advance from every position you take: Try on new perspectives and learn from what you meet there.

And, if we can abandon our missionary zeal we are less likely to be eaten by cannibals: Certainty is a formula for being unkind. It will also help create contention. Please no “helping,” just service.

Beloved community is the fabric that holds the night, however dark. It reflects the light, but it holds the dark, and in doing so cradles the deepest capacity for transformation of the heart. Our many traditions are threads which weave this tapestry of potential. On the one hand they tug on the edges and knit them across the great wide heart at the center, not to drown the distinct differences or dull the vibrant hues of each tradition, but to hold them in place so they can do their work—The Work—of continuing this immense earthly experiment which is in peril. In addition, the threads of community extend beyond the edges to communities and people who are unseen, maybe without a voice, and lost in echo-chambers of their own. In this way we have a chance to reclaim bits of broken and scattered hearts for the gold they contain.

And this noble experiment is in trouble—politically, socially, culturally, biologically, and artistically because we are at a crossroads of imagination in its truest sense. Can we imagine big enough, deep enough, wildly enough to save ourselves? Can our imagination grow beyond the bounds of practical problem solving or endless technologizing and reclaim the deep responsibility to each other and for each other in the face of such bewilderment?

How will our children ever learn to be grace-filled humans beyond their tablets and phones? How can we teach character and emotional intelligence, not just learning to be tech-savvy? How we use technology is making a difference in radically disturbing ways as we see every day. And finally, can we demonstrate with our own lives and through our personal relationships, and with full conviction, that a Tweet is not a kiss on the cheek, an email is not a whisper in your ear, and a Facebook friend request is not an outstretched hand. Language was the first virtual reality, let’s practice with it skillfully.

Will we leave the next generation a world they will truly want to occupy, and one in which they can actually live and thrive? These are real questions, and it appears that our wisdom traditions may hold more of a key to survival than our evolving technologies and complex global economies. Because without groups like iACT, it is all simply two- dimensional—a flat, well explained, detailed and digitalized map of prediction and knowledge that is barren — devoid of wisdom and drained of compassion — good at the bottom line but deadly for the vulnerable living beings we are.

And one last thing. We require more beauty. Returning to our silent hosts in the garden (the sculpture), we are reminded that we are surrounded by works of art. Acts of kindness and works of goodness are beauty incarnate. Beauty is visible, palpable, in moments when human beings “reach across the mystery to each other,” as Krista Tippet has said. Our most beautiful work is removing barriers to love - but isn’t that what spirituality is for and what social action brings to life? Elizabeth Alexander, speaking boldly on that beautifully crystalline inauguration day in 2009, stated in a public, political arena that “love is the mightiest word.” And so it seems to be.

How can we come to love the full force of life energy which terrifies us? And how do we face our deepest longing alongside our greatest terror — loving and being loved? What if beloved community is already the Truth in which we are immersed — a literal field of benefaction which we can awaken to, like fish swimming in water. What if our job is to realize it, to embody, and to live it? In the Buddhist tradition we take refuge — we endeavor to “fly back” as the root of that word implies, to come home. To what? The Buddha’s earliest teachings were clear, sangha—spiritual friendship and beloved community— the heartbeat of spiritual life.

And what does this look like in action? Each person here could tell a story of how some small action has made a difference. Several years ago I was working with Palestinian and Israeli women in a powerful and raw encounter at Esalen through a wonderful foundation, “Beyond Words.” These women were asking the same questions I am posing tonight in the face of seemingly unending generations of strife. One woman, a kindergarten teacher, told me that she felt helpless, as if anything she could do would mean nothing against the ancient hate and enmity. But she told me how she taught her students to sing, and her tiny choir went out from the classroom and sang to the soldiers along the wall dividing the Jewish and Arab settlements. She told me how the soldiers put down their guns and turned toward the children, helpless against their call, their tiny, tender courage. This one small thing did not stop the deep conflict but it interrupted the damage, at least for a moment. And every moment counts.

The poet W.S. Merwin, nearing 90 years old, taking care of his garden and his grove of endangered palms on the north shore of Maui, spoke about the pain of the earth’s destruction. He then said, “On the last day I want to be planting a tree.” This is what he does for the good of the earth, so he will do it no matter how things appear to be going. He is not blind to the massive destruction of the planet. This is his small thing he can do, despite the fear that it will make no difference. Why do we do good? Because it is what we do. Because we must!

Rilke again…

God speaks to each of us as he makes us,

then walks with us silently out of the night.

These are words we dimly hear:

You, sent out beyond your recall,

go to the limits of your longing.

Embody me.

Flare up like flame

and make big shadows I can move in.

Let everything happen to you: beauty and terror.

Just keep going. No feeling is final.

Don't let yourself lose me.

Nearby is the country they call life.

You will know it by its seriousness.

Give me your hand.

Thank you very much.